Cricket

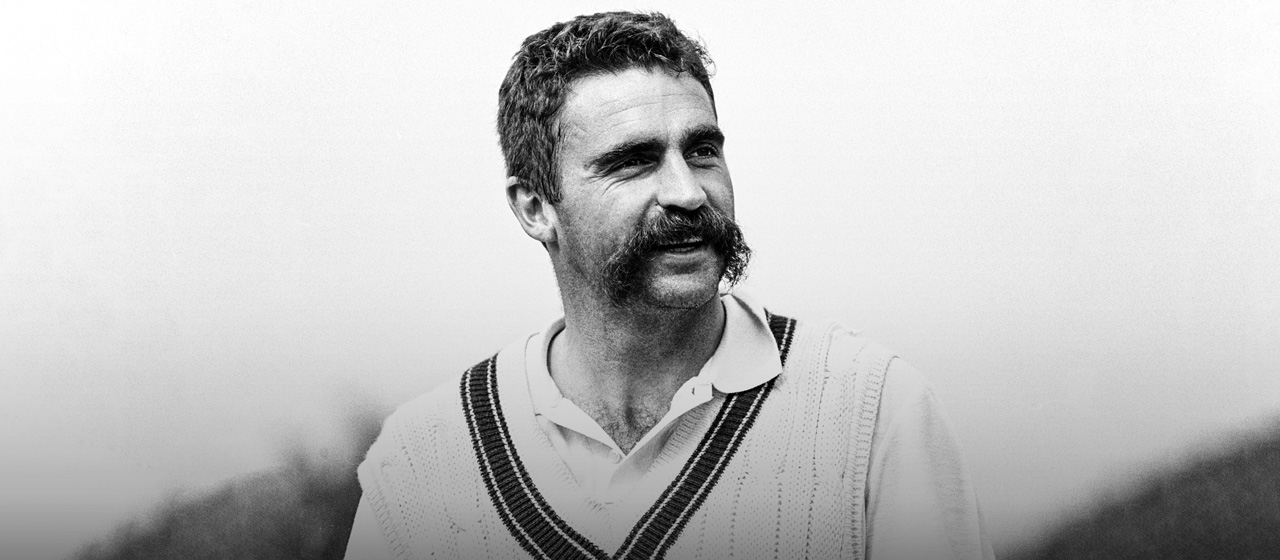

Botham sledge that drove me

It was the first time I had got in trouble with my wife for not going out! Earlier that day we had retained the Ashes with victory in the fourth Test at Headingley. We had celebrated in the changing room and at the team hotel, with the plan to then meet our wives and girlfriends at a nightclub in Leeds, but I never made it.

The rest of the team headed out to continue the party, while I retired to my bed. I had been bowling for three days; my right knee, which caused me problems throughout the tour, was in real pain and my whole body was aching. I was happy, but exhausted, and by midnight I was fast asleep.

This Test at Headingley was the 49th of my career, which was pretty good because eight years earlier I thought I would only play once for Australia. In December 1985 I played in my first, and I assumed last, Test against India at the Adelaide Oval.

After being out for a duck in our first innings, I then finished with match figures of 1-123 from 38 overs. It had been a big step for me, clearly too big. India made 520, with Sunil Gavaskar finishing on 166 not out, and I could do nothing to stop them. I was dropped for the rest of the series and overlooked for the tours to New Zealand and India. I thought my international career was over.

But eleven months later, after a good start to the season with Victoria, the selectors decided to give me one more chance against England in the first Test at Brisbane. The Poms were favourites to retain the Ashes with an experienced team, while we were still rebuilding after the departure of several players on a rebel tour to South Africa. By the time England had reached 4-198 in their first innings at the Gabba, I had trebled my total of Test wickets by claiming Mike Gatting and Allan Lamb and was feeling pretty good about myself. Then Ian Botham arrived at the crease.

The England all-rounder gave me a terrible mauling, hitting me everywhere. I had no answers. If I pitched it up he just hit through the ball, if I bowled short he would hook or pull it. My inexperience was being ruthlessly exposed. A couple of his sixes went a long, long way. ‘Merv, these are going so far they might get frequent flyer points,’ laughed Dean Jones as he went to fetch them.

It got ugly when Botham made 22 runs from a single over, scoring 2, 2, 4, 6, 4 and 4 off me. I am embarrassed to say it was a record for the most runs off an over in an Ashes Test. I would check the record books, desperately hoping some poor soul had been worse, and while I found there was once 24 scored off an over, it was from an eight-ball over.

At tea on the second day, after Botham was finally out for 138, I was sitting outside our changing room watching the rain come down and trying to understand what had just happened when Botham came out of England’s room. ‘You probably don’t remember me,’ I said to him. ‘But I was at a coaching clinic you did at Benalla when you played grade cricket here in the 1970s.’

‘Did I give you any good advice?’ he asked. ‘I told you I wanted to be a fast bowler, but you said I should take up tennis or golf because they were more enjoyable and better paid.’ He got up to leave, turned to me and said, ‘You should have listened to me.’

I would think about those words during the next six years as I established myself as a Test player. I took 8-87 against the West Indies at Perth a year after being humbled in Brisbane, and then regained the Ashes in 1989 against an England side containing Botham. I had proved I was good enough to play for Australia.

By the end of 1992, after over 40 Tests and 170 wickets, I was beginning to feel worn out. I was only 31, but I felt older as I struggled with my weight and fitness. We were facing the West Indies that summer and Courtney Walsh said I looked over the hill. He could see the pain on my face as my knee constantly ached.

I got through against the West Indies OK, but I still had a tour to New Zealand to navigate before having surgery. My weight was putting my knee under even greater strain, physio Errol Alcott and our team manager Ian McDonald asked me to stand on some scales. I refused to get on. They told me it was in my contract and for every kilo I was overweight I would be fined. I asked if I lost some would I get a rebate? They weren’t amused and kept asking me to jump on, so I thought, ‘Right, I’ll do just that.’ I took three steps and jumped on. The scales disintegrated.

On my return home I finally had an arthroscopy, which is minor keyhole surgery to clean up my knee. I hoped this would be enough to get me through the long Ashes tour of 1993.

After arriving in England it wasn’t long before my knee began to bother me, and I knew it was going to lurk around all tour. In those early weeks I didn’t train much, instead spending a lot of time getting treatment. But this didn’t stop me heading off to watch a rugby league final at Wembley with Wayne Holdsworth.

Afterwards we had a few beers and made our way to a nightclub where, to my horror, my knee locked up on a dance floor. Then a few weeks later I was walking on to the field at Northampton and it happened again. It is frightening when you suddenly can’t walk.

BALL OF THE CENTURY

At the start of June the Ashes began with the first Test at Old Trafford. Our openers, Tubs [Mark Taylor], with 124, and Slats [Michael Slater], with 58, got us off to a great start, but the rest of the guys failed to match that and we were all out for 289.

Early in England’s reply Michael Atherton nicked me through the slips. ‘In four years you’ve got no fucking better,’ I snarled. ‘And I see in four years you haven’t got any new lines, Mr Hughes,’ he replied. Don’t worry about Atherton, he gave as good as he got. His sledging was always more subtle and intelligent than my basic stuff. But I won the first battle of the summer when I got him out for 19.

Towards the end of my opening spell, England were 1-80 when Allan Border decided to bring on Shane Warne at the other end. With his very first delivery, Warney produced the ball of the century, to dismiss a shocked Mike Gatting. I was down at deep backward square leg and as Gatt trooped back I walked in and asked Ian Healy, ‘What did that do?’ ‘It pitched off and hit off,’ he said. I thought Gatt had played for the spin and it had gone between bat and pad. I turned around and watched a replay on the big screen. Heals smirked, ‘Well, OK, it might have pitched outside leg.’ I couldn’t believe what I had just seen.

I played in Warney’s Test debut against India at the SCG in January 1992. He got 1-150, and I was delighted to meet someone who had worse bowling figures on their debut than me. I had known him since he had got in to the Victoria team with me, and I quickly realised he had a rare talent. I was fascinated to see how far he could go, but while I knew he was good, even in 1993 I don’t think anyone realised what he was going to do in Test cricket: take over 700 wickets and become one of the game’s legends.

As a fellow Victorian, I took Warney under my wing on the tour to England, but that didn’t make him immune to the odd joke. During his second Test in January 1992 we were sharing a room in Adelaide. Around midnight we ordered some sandwiches and drinks from room service. After polishing them off, I told Warney to roll the service trolley down the corridor and leave it outside someone else’s room, so none of the team management knew we had been greedily stuffing ourselves. He got out of his bed naked, and as soon as he was out the door I locked it. You should have heard him pleading for me to open it. I think he had to get someone from reception to let him back in.

SIMPLE VERBAL INTIMIDATION

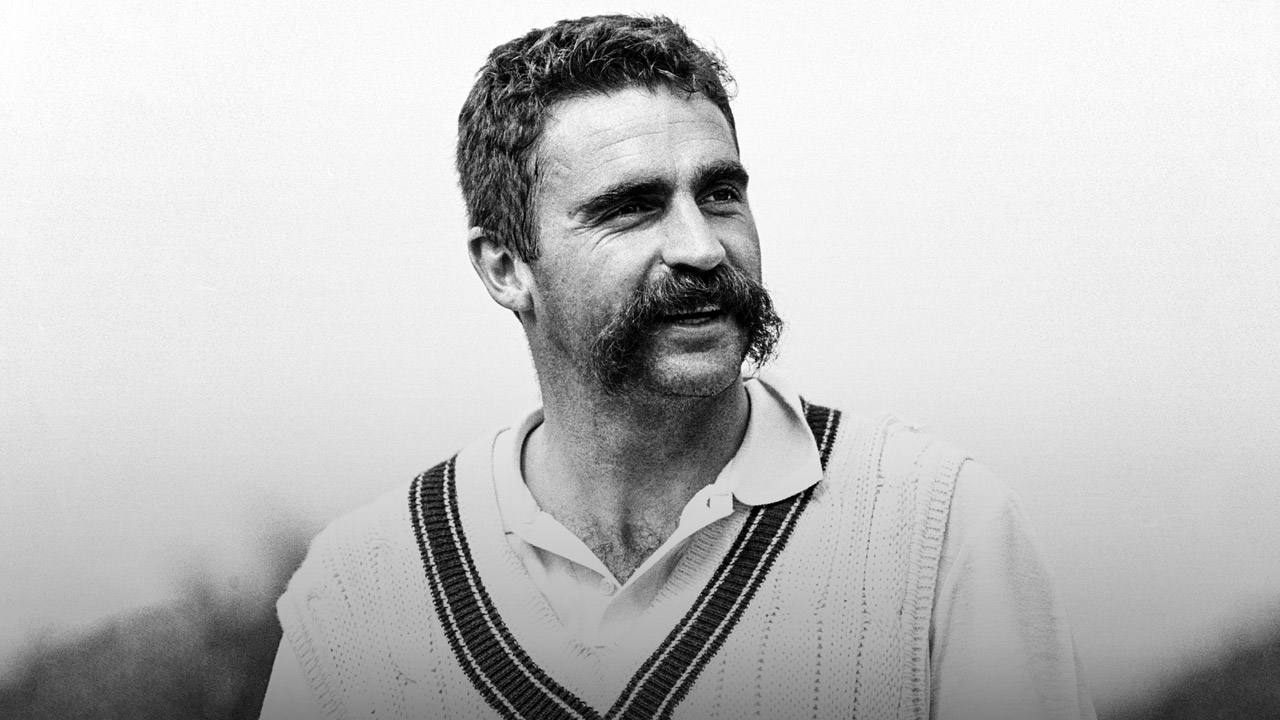

While I didn’t have much joy sledging Atherton, I got right under the skin of Graeme Hick. He really copped it. It wasn’t his fault, he was just a victim of circumstance. When he played for Queensland in the 1990-91 season he was compared with Sir Donald Bradman because of the amount of hundreds he had already scored in county cricket in England. That really riled Australians. How could this bloke who had never played a Test be spoken about as if he was as good as Bradman? We were going to get him.

I would shout all sorts of crap at Hick to unsettle him. It was old fashioned sledging, just simple verbal intimidation. If you can get the batsman more worried about what you are saying rather than the next ball then you are halfway to winning the battle.

Sledging had always been a crucial part of my armoury. If you were facing me then you were the person I hated most in the whole world. Whether I was playing for Footscray or Australia, sledging put me in control, and got me inside the batsman’s head.

In England’s first innings Hick never looked at ease as I went at him. On 34 he cut a ball straight to Border at point, and was mine. I also picked up the wickets of Phil Tufnell and Chris Lewis to finish with 4-59. England were all out for 210, still 71 runs behind.

We stretched our lead far beyond that with Ian Healy making a century as we declared on 5-432 in our second innings to set England a target of 512.

During their run chase I had Hick caught behind by Heals. It was obvious I had cast a spell on him. Just a bit of sledging and he immediately looked uncomfortable. After that wicket I went up really close and shouted in his face. There is a famous picture of it, so people ask, ‘What did you say?’ Nothing. I just yelled at him, it was one big ‘ahhhhhhhh’. I wanted to stay in his head.

I grabbed the last two wickets of the game to finish with 4-92, and we won by 179 runs to go 1-0 up. Four years earlier I would have been the first one out to the pub, but I turned down a night out in Manchester to get in to my bed, shattered, but very happy.

More about: Ashes | Australian cricket team | England | Shane Warne | Steve Waugh | Test cricket

Load More

Load More