Cricket

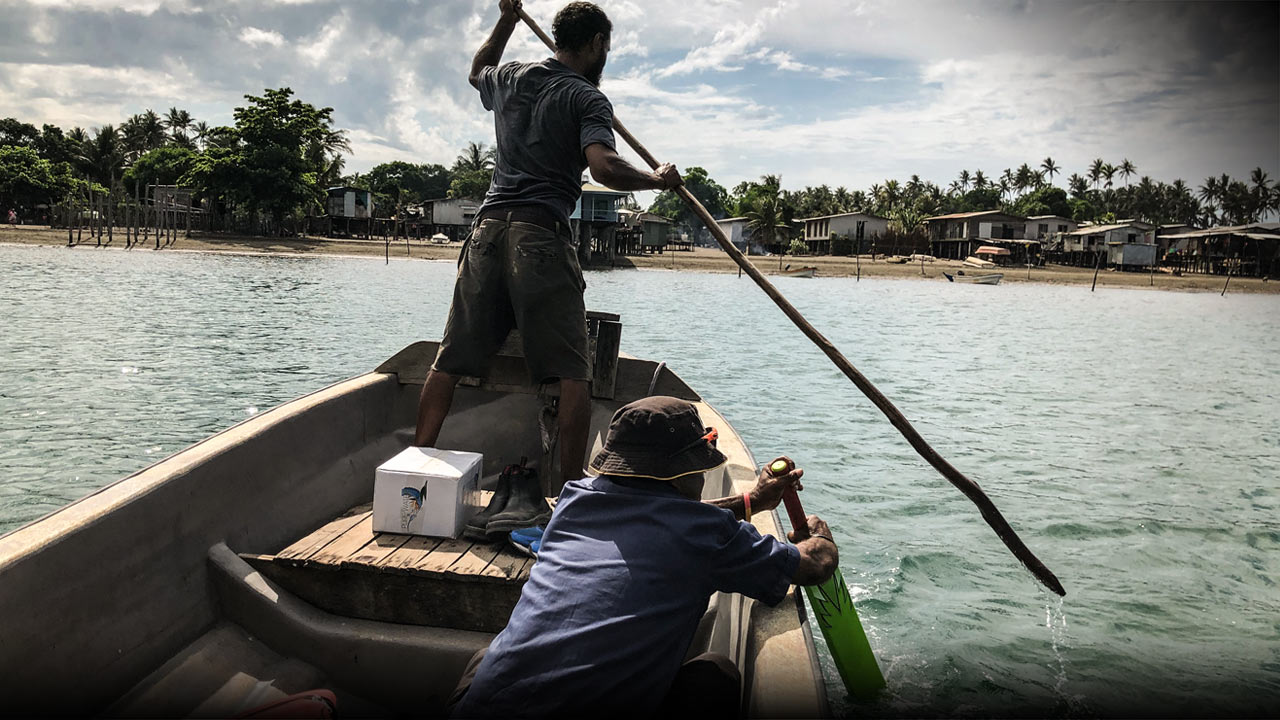

Milo bats for oars

I travelled to a small village about three hours from Port Moresby for a coaching clinic last year. It’s where a couple of the PNG Barramundi players come from.

At the end of the long drive we had to cross a small lagoon, about 600 metres wide, to reach the village. A bloke came across to pick us up in his motorboat and we threw all the kitbags in and climbed aboard. Halfway across the lagoon, old mate’s boat ran out of petrol.

He was doing everything to try to squeeze the last drops out of the empty fuel tank. And no wonder. Forget Work, Health and Safety up here – there were no oars in our boat.

So we broke out the plastic Milo cricket bats we’d brought over from Australia and used them to row ourselves the rest of the way across the lagoon to get to the training session.

That sums PNG up for me. You can’t get the shits with it. You just laugh and roll with the fun times. There are days when it’s a bit frustrating, but you can’t do much about it. You just get on with it.

Daily struggle to survive

I’ve been Papua New Guinea’s national team coach for 18 months and cricket here has never been a better story. We’ve just qualified for the T20 World Cup in Australia, a historic moment, and earlier this year we retained our ODI status.

That was a life-changing moment for a lot of people because of the funding that comes with the status, and what it provides. That was an incredible day.

The moment PNG qualified for the #T20WorldCup!

Look how much it means to them! pic.twitter.com/F2PM64vAcn

— T20 World Cup (@T20WorldCup) October 27, 2019

It can be a tough life for my players. Most of them live in houses that don’t have running water. Not everyone has power. It’s a daily struggle to survive up here.

The money they’re earning from cricket might be feeding 15-20 people in a household. So cricket isn’t necessarily their main focus; surviving and feeding their families is.

We had an issue at the cricket ground recently where one of the security guys, who probably makes $1.50 an hour, had obviously neglected to pass on his paycheck to the family and they were chasing him around the cricket complex with machetes.

I was thinking, ‘I don’t remember seeing that in the brochure.’

It’s a special bond

If you look at the countries we will be playing against at the T20 World Cup next year, and what it’s like for them, our experience is completely different.

Almost all of our players live in Hanuabada, the ‘big village’ or ‘HB’ to the locals in the Motuan tribe who call it home. It is basically a shanty town built over the water on stilts, started by the Diggers after WWII as a thank you for the locals’ help during the war.

There is a lot of cricket interest in the village and it’s where most of our players grew up. The others have moved there to be close to their teammates.

I’ve never before worked with a group of people who are like a big family in the way these guys are. Through thick and thin and all the challenges they face travelling the world having come from this place, they stick together.

I’ve been in some really good cricket teams over the years but I’ve never seen anything else like this. They share a special bond.

Regaining ODI status and qualifying for a @T20WorldCup in the same year…

What a year this has been for us!#T20WorldCup pic.twitter.com/thpEMmPxwU

— Cricket PNG (@Cricket_PNG) October 28, 2019

Nutrition is a key issue

Most people from member nations wouldn’t have an understanding of cricket in this world.

I knew it a little better than most with the contacts I’d had with PNG over the years through some good mates who had coached here.

The quality of the players and the quality of the cricket is very good, which was a pleasant surprise.

My previous job was with the Australian women’s team and there was a huge difference coming from the National Cricket Centre in Brisbane with the gyms and pools and physio facilities. Up here we only have one turf oval in the country, one set of turf nets and no gyms at the ground.

When I was coaching with the Indian national team we would use a full box of turf cricket balls at every training session, worth about $1500. In PNG, if we get hold of a box of balls we’re trying to make that last for two or three months.

We have 15 men and 17 women on fulltime cricket contracts. We’re lucky the cost of labour here is very cheap compared to Australia and, compared to the general population, the players can make a reasonable living from the game.

They’re by no means wealthy. And wealth is an interesting thing to judge up here because it’s not just an income for their immediate families, it’s for their parents, brothers’ and sisters’ families and sometimes even more.

I was talking to one of our quicks about getting his nutrition right in the off-season phase. He lives with 12 other people and his cricket income is providing food for all of them.

Nutrition is a key issue. Getting the quality of food up here is difficult, and expensive. When you are feeding 12 people you can’t afford to buy 12 rump steaks, so in many cases dinner might be a huge bowl of rice flavoured with tomato sauce or a two-minute noodle satchet.

Despite the obstacles we’ve put together a really good strength and conditioning program with two fulltime staff. Stephen Schwerdt from the SACA has been brilliant in putting together our program.

Natural skill isn’t an issue. There are players here that are as good as any I’ve seen running around. I had Tim Coyle, the former Tasmania coach, working up here and he rated some of the fielders in PNG as the best naturally uncoached players he had seen.

Our biggest challenge is the amount of cricket they get to play and developing the mental aspect of their games. Their cricket education and knowledge is well below that of players in Australia who get to play hard club and first class cricket on a regular basis.

On the field, they’re very noisy because they love playing for their country and each other. They’re always laughing and their celebrations are some of the best I’ve seen.

Sledging the opposition is not in their nature at all. The coastal people here in PNG are mild mannered. We’ve worked on getting them to poke their chests out, not necessarily being verbal but to stand up for themselves and show they’re not intimidated by the opposition. They’re good with that and won’t take a backward step, but they’re not going to get stuck into someone.

There are 800 dialects here and not all of the players speak English, so communication can be an issue, no doubt. The boys are shy but you learn to communicate simply and slowly, and I don’t mean that disrespectfully.

Coaching in India was a great learning experience for me. You get to know a couple of guys who speak English well and take it from there.

I had an issue in India with one player who spoke Bengali. He would never raise it as a problem face to face, he would always say he understood, but it was used as an excuse by people away from the team when they let me go. That’s the politics of Indian cricket.

I always use another player or a staff member who speaks both if I feel the message isn’t getting across. And I always tell players it’s not their problem or fault if they don’t understand me, it’s me because I’m a guest in their country and they should never be embarrassed by not understanding me and to come and tell me and we will find a way of getting the message through.

More about: Adelaide Strikers | Big Bash League | Coaching | International cricket | Papua New Guinea | Resilience | T20 | T20 World Cup

Load More

Load More