Golf

We didn’t even have range balls

It doesn’t matter what age I am, what I’m doing or where I am in the world: the week of the Open Championships is always special.

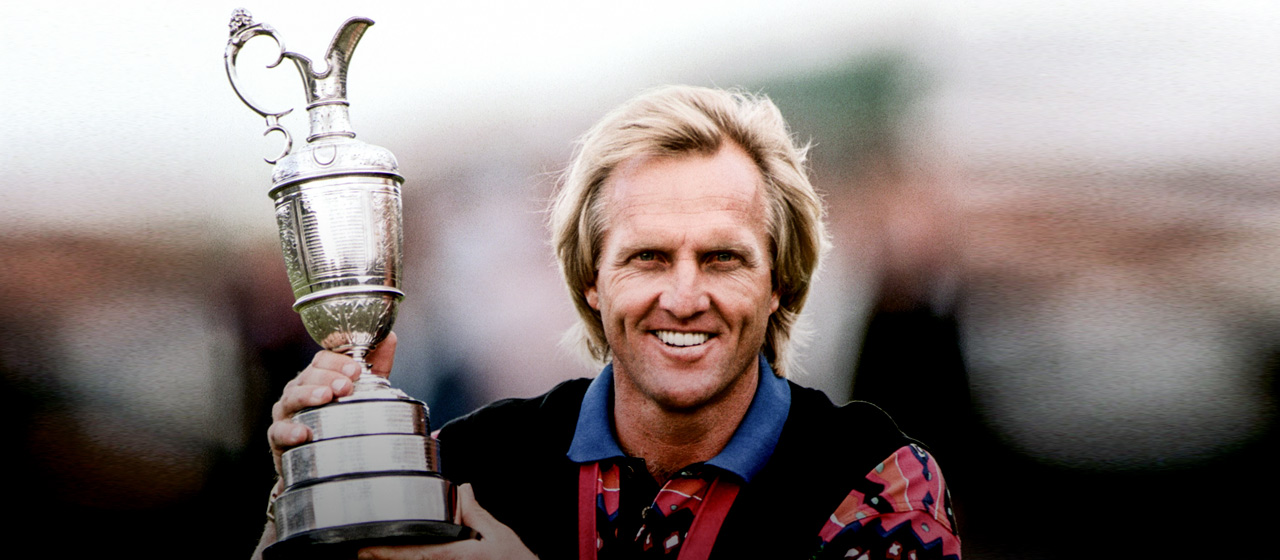

People often want to talk to me about Turnberry in 1986 and Royal St George’s in 1993 and that’s fine. Both are treasured memories, obviously. I’d throw Royal Birkdale in 2008 into that mix as well as others.

But the triumphs alone don’t represent the full experience of the Open.

My first Open Championships was in 1977, the year after I turned professional and six years after my mum, Toini, taught me how to play the game around the courses of Townsville and Brisbane like Magnetic Island GC, Townsville GC, Virginia GC and Royal Queensland GC.

It was a different world back then.

I don’t think enough mention is made of the vast distances involved for the non-US, non-European players. Think, for example, how much harder someone like Gary Player had to work for his success, travelling out of South Africa, compared to the players from his era from the States or England.

The same applied for Peter Thomson. Thommo was a generation or two before me, but he instilled the values and the work ethic that so many Australian golfers, myself included, would follow through the decades. He didn’t just win five Open championships. He showed us you could succeed on the global stage despite being from the other side of the world.

It was sad to lose him last month. He’ll be on the minds of many people at Carnoustie this week.

Life on the road was tough when I first joined the European Tour in 1977.

I had to plan everything meticulously – flights, transfers, connections, hotels, practice times, the lot. I would fly however-many-hours across the world, lug my suitcase and golf bags off the plane, jump a train or a bus or a cab and make my own way to the tournament I was playing.

The more tournaments I won, the more help I could afford to arrange logistics. But those early days? You survived on your own. No charters, no private jets, no limo drivers waiting with your surname on a little white board. Just me and a whole lot of luggage.

Players today might laugh when they hear this, but we didn’t have range balls.

I would save every ball I played with, put it in my shagbag and keep it for practice down the track. It wasn’t just the shagbag I was carrying around either. In the early days, I travelled with spare shafts, spare glue, spare grips and more.

We didn’t have golf club facilities, either. There was no one around to help for the most part. If you were on the road and you broke a shaft, what did you do? You fixed the bloody thing yourself.

It could be quite humiliating at times. Some of the tournaments were played at courses where members wouldn’t allow pros in the locker room. So I’d be out there in the carpark getting ready, putting on shoes and such. The mentality of golf in Europe in the ’70s was that it was an elitist sport and pros at the time were not looked upon as the pros are in this modern era – idolised and revered. It wasn’t as much fun.

But here’s the thing: those same experiences have ended up being some of the most important of my life. They were the staple, the backbone, of everything I would go on to achieve in life. They instilled in me a sense of self-reliance, provided a template for the benefits of hard work and imbued in me a curiosity about people, cultures, languages and foods.

For a kid from far north Queensland, those experiences expanded my view of the world dramatically.

So many of them centred on the Open Championships.

WINNING IN DEFEAT

The sound of the ball off the clubface at The Open is different to anywhere else in the world.

It’s hard to describe it.

It’s the tight fairways, the very firm soil, the hardness of the sand. The sandbelt courses in Australia have those couch grass fairways and they can get tight, but the sound and feel of the club hitting the turf is just different at The Open. I felt like you could manoeuvre the ball more playing off the turf at The Open than at any other tournament in the world.

Every Open was significant. They all shaped me in some way. I was very fortunate to lift the Claret Jug twice, but there were tournaments I didn’t win that had just as big an impact on my life.

Losing the play-off to Mark Calcavecchia at Troon in 1989 was one of those tournaments. I shot 64, starting with six straight birdies, in the final round to join Mark and Wayne Grady in a play-off, the first time the four-hole play-off format was used.

I birdied the first two play-off holes but lost.

Would I have won under the former play-off system? Who knows.

The tournament Nick Faldo won at St Andrews in 1990 was another. That was a real gun-slinging match. I absolutely loved going toe-to-toe with him over those 72 holes. But he came out on top.

Even when I did break through at Turnberry in 1986, it came after I had led through three rounds at the Masters and US Open (it was the same at the PGA Championship afterwards, too). There was a big build-up coming into the final round at Turnberry – from the media, from the fans, from my family and friends and from myself.

I won ten tournaments that year, including six tournaments in a row in different countries to close out ‘86. But the Open Championship was my only major. Convert one or two of the others and it could’ve been an extraordinary year. In the end, I had to settle for a very good one.

There was nothing I could do about it. I learned from the experience and moved on.

Players today might laugh when they hear this, but we didn’t have range balls. I would save every ball I played with, put it in my shagbag and keep it for practice down the track.

But probably my favourite ‘non-winning’ memory of the Open Championships was at Royal Birkdale a decade ago. I was 53 at the time. I hadn’t played much golf in the lead-in. No one was looking to me for much.

When I arrived at Birkdale, I looked at the seven-day weather forecast. It wasn’t very good. That was perfect for me. It was going to be about feel and trust, not using your yardage book on every shot, and drawing on my 35-plus years of experience. The winds were so strong I was hitting five-irons from 120-130 yards, bump-and-run shots. It was brutal. No one finished under par for the tournament.

After 18 holes, I was one shot back. It was the same through 36 holes. After 54 holes, I was in the lead – the oldest ever to do so at the time. It was pure links golf.

I ended up in a tie for third behind Padraig Harrington and Ian Poulter, but the experiences and the lessons from that tournament live with me to this day.

It told me that with the way technology is these days, coupled with the big advances in physical fitness, someone will win a major championship in their 50s.

When I hit the driver today, at the age of 63, it goes further than when I hit the ball in the 1980s.

It won’t be long until someone goes a couple better than I did at Royal Birkdale in 2008.

THE LESSONS OF TURNBERRY & ST GEORGE’S

It might sound a little odd, given I ended up five shots clear of Gordon J. Brand, but I didn’t feel any sense of relief at Turnberry in 1986 until my approach shot hit the green on the 72nd hole.

But even then there were things to contend with, things on my mind.

These days, security keep galleries and players well separated. Not in ’86. Back then, I walked through hundreds, maybe thousands of spectators to get to my putt on the 18th.

I count it among the greatest moments of my life, right up there with running across the Sydney Harbour Bridge with the Olympic torch in 2000. People were so excited, smiling, patting me on the back. It was beautiful and one of those unexpected experiences in life that catches you by surprise and fills you with emotion. Yes, a little rough, perhaps, but beautiful all the same.

That said, there was still a job to do. I wouldn’t say I had tunnel vision – I still wanted to acknowledge everyone, look at them, thank them for their support, make them feel part of the event – but neither could I get too caught up in it.

I walked through hundreds, maybe thousands of spectators to get to my putt on the 18th. I count it among the greatest moments of my life.

I equate it to giving a speech today. Whether I’m delivering it to one person or 10,000 people, I approach it the same. There’s a job to do.

What’s around you doesn’t change that. In the case of putting out on the 72nd hole at Turnberry, I had to approach it like any other putt, even though the walk to the green was unlike anything I’d experienced in my life to that point.

I didn’t truly relax until a few minutes after my final putt.

I had been thinking about signing my scorecard and not screwing that up. That was definitely on my mind on the 18th. Once it was done – and I’d checked and rechecked it – the emotion washed over me. All the hard work, setbacks, dedication, commitment, travel had all been worthwhile.

I’d achieved it. I’d won a major.

St George’s in 1993 was totally different.

When I walked up to the first tee on the Sunday, I knew there were maybe eight players who had a chance to win that tournament. The course was giving up good scores all over the place. The leaderboard had a lot of names with 63, 64 next to them. It was going to be a shootout.

The big moment for me was when I birdied the ninth hole to take a one-shot lead.

I said to myself, ‘This is what I want.’ It’s like any athlete in any sport: you want to be the full-forward lining up the winning goal with a few seconds left, the quarterback with the ball in his hands on the final drive, the point-guard launching a buzzer-beater for the win.

In my case, I had the lead with nine holes to play. My fate was in my own hands.

I didn’t take my foot off the accelerator from there.

The most enduring memory of that final day didn’t have anything to do with a particular shot or score, however. It was a conversation with Gene Sarazen on the 18th after the tournament was over.

Gene came up to me, an absolute legend of our game, and said, ‘I was in awe of your golf.’

I have a photo I am proud of, taken at that moment, where I am bowing to Gene shaking his hand and showing the ultimate sign of respect for a legend of the game.

It was incredible. When your peers, younger or older, look at your performance and go, ‘Wow, that was pretty impressive,’ you can’t help but feel good about that.

Coming from Gene, it was a whole other level.

THE SEXIEST TROPHY IN SPORT

Carnoustie is a very, very demanding driving golf course. I don’t know how the R&A has set it up for this year’s tournament but, on a scale of difficulty, I’d put Carnoustie in the top three toughest courses I’ve played.

The rough was vicious, the fairways were extremely narrow and you had to know how to drive the ball. And then there was the wind.

Dustin Johnson is a great driver of the golf ball, maybe the longest and straightest driver there is today. If his putter stands up to the test, he’s got every chance this year.

The same goes for Jason Day. He has a phenomenal short game and a great putter, which you need at Carnoustie. His consistency level has not been there this year, but if he’s on, he’s a threat.

I’m disappointed to see where Adam Scott is. I haven’t spoken to him in a while so I’m not sure what the specific issues are in his game, but he certainly has the pedigree to win it if he can rediscover his form of the past. And Marc Leishman always flies under the radar. I think he will win a major one day. He’s a consistent performer and his skillset is excellent. Then there are a plethora of other great players who all equally have a chance – Rory if he, too, can reverse his poor putting, Brooks, Tommy Fleetwood would be the home favourite, just to name a few.

I’d put Carnoustie in the top three toughest courses I’ve played.

They’re all playing for the sexiest trophy in all of sport.

I really mean that. Just look at the Claret Jug. The size of it. The shape of it. It’s not overpowering or gawdy. It’s just beautiful. It’s elegant. When I won it, the jug was separated from the base. It was in two parts. Now they’re attached. To me, it’s perfect.

When you have the ability to take that trophy with you around the world for a year, so everyone can feel and touch it, it’s a truly wonderful experience. I wanted everyone to see it. People from different countries. People who wouldn’t normally get the chance to attend The Open.

It was a part of me for those 12 months.

One of the elements that makes it so special is the British golfing public it represents.

They truly appreciate the game and those who play it. Their knowledge is excellent and their appreciation for links golf is appreciated by ALL players. They come out in the most adverse weather conditions. You can hear what they’re saying in the galleries. They really know their stuff.

It’s a pleasure to play in front of people like that.

More about: Adam Scott | British Open | Greg Norman | PGA Tour | The Masters

Load More

Load More