Boxing

Escaping the noose

I won’t mention the guy’s name here.

I’ll just say that he’s a white fella and he was in with Michael Dickie and Timmy Ellis and a few of the others in the Team Mundine inner sanctum. I didn’t know him until he came up to me after a fight not long ago and introduced himself.

This is what he told me.

He had decided to end his life. He had grabbed some rope, made a noose and placed it around his neck. The depression was too much for him to take any longer. He was ready to step off and leave this world.

Done.

Then his daughter walked in on him. She wasn’t very old. Maybe 11.

She was very upset. Who wouldn’t be? No one that age should have to see something like that.

Through the shock and the tears she said to him, ‘You can’t do this, dad. You can’t go. You promised me you’d take me to meet Anthony Mundine.’

He fought it for a moment. But then he stopped and thought.

‘You’re right,’ he said.

He removed the noose from around his neck and stepped down. She had saved his life.

When they both came to one of my fights and told me that story, man, I just broke down. I cry when I think about it now. There is so much struggle, so much pain, in the world. To think that I played some small part in keeping that fella from taking his own life is more important to me than any world title or famous win.

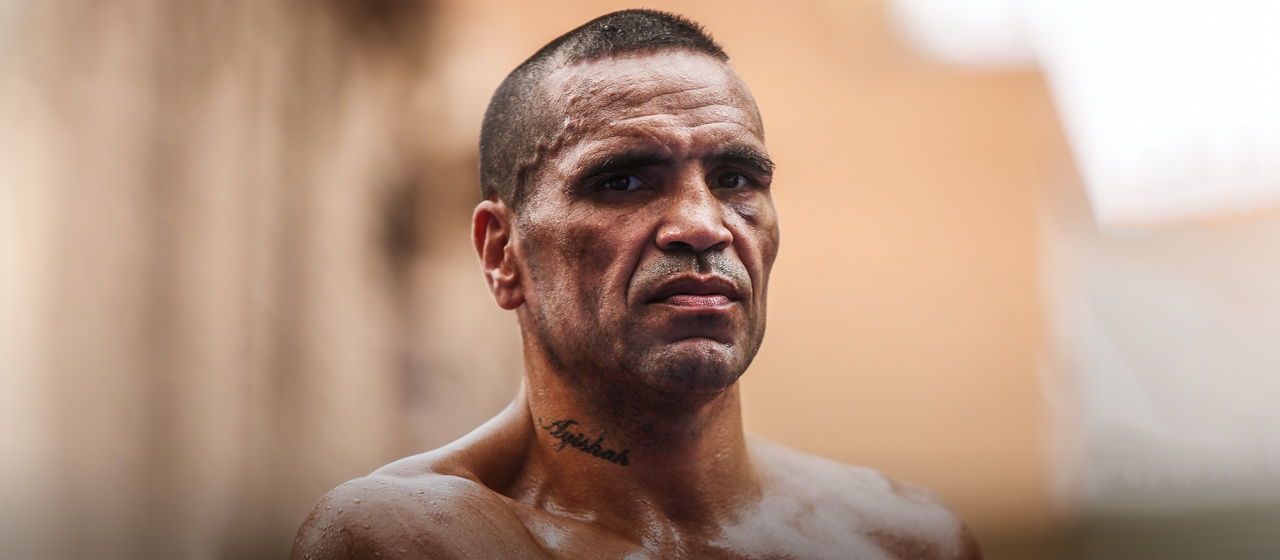

I’m 43 and almost at the end of my boxing career. I haven’t been in much of a reflective mood lately – there’s still a big fight to prepare for – but that hasn’t stopped people from coming up to me and asking, ‘Choc, what’s the highlight of your career?’

It’s this stuff. The social stuff.

I can’t tell you how many times people have come up to me through the years to tell me about the positive impact I’ve had on their lives, or someone close to them. Black fellas and white, city folks and people from the bush. The messages I’ve been pushing from my platform all these years have reached their ears and helped them turn their lives around, one way or other.

I want my legacy to live on beyond my lifetime, Inshallah.

I want your great grandkids to know about me long after I’ve gone.

I want them to know I made the world a better place.

THE POWER OF MY VOICE

Sven Ottke gave an interview to The Ring earlier this year.

He’s one of the greats, an undefeated world champion, and the man who handed me my first defeat in my 11th professional fight in Dortmund 17 years ago.

They asked Ottke to name the toughest fight of his career. He said it was the one against me. He said I was the fastest, smartest, most skilful fighter he ever came up against with the best footwork, the best jab and the best defence.

I was still playing for the Dragons the year before we fought!

Ottke had more successful title defences than I’d had fights – professional and amateur combined – when we met. Looking back, I was out of mind taking that fight at the time I did. And I didn’t make it any easier for myself once I got to Germany. I didn’t do any sparring over there beforehand. Nothing. I was stubborn. No sparring, no road runs. I had these new training methods and I was determined to see them through. I guess I learned the hard way.

As you get older, you become more mellow.

Sometimes I look back at some of the things I said and did during my career and realise how crazy it probably all came across. I’ve always had that much belief in myself. I was young and brash but I wasn’t arrogant in the way I lived my life. I’m the most approachable person you’ll ever meet. Ask anyone who knows me.

In some cases, I could’ve articulated myself better. The statement I made about September 11 before the Ottke fight was one of those times. Things came out raw and uncut and the media did what they do. They took an angle and sent it all around the world.

I meant well. I was trying to point out a broader issue – the west, superpowers trying to take over everything and how that was playing out around the globe. I’m not for killings. Of course, I don’t want innocent people to die. Islam teaches you that you can’t kill one human being, let alone many. It’s like killing the Almighty.

Whether you’re from America, Africa or somewhere in between, I love all people the same.

Some of the controversy in my life has been brought on by things I’ve said. Some is just because of who I am. Aboriginal. Muslim. A man unafraid to fight the system.

I want your great grandkids to know about me long after I’ve gone. I want them to know I made the world a better place.

I discovered the power of my voice early. Khoder Nasser gave me The Autobiography of Malcolm X when I was just making my way in rugby league and it made me question many things. I got deep with this book. I was never a very patient reader, but I couldn’t put it down. I asked a lot of questions of some of my Muslim brothers about the world, and life, and religion. I knew I had found my answer in life.

I took my Shahadah when I was 21.

It helped give me the strength and courage to speak about injustices and highlight the plight of my people. I was only just starting out at the Dragons, and a youngster was expected to be quiet and polite back then.

But, nah. That was never going to be me.

STICKING TO MY GUNS

When I quit footy for boxing, everyone thought I was insane.

I told dad.

‘What are you doing?’ he said. ‘You’re crazy, mate. Boxing’s dead.’

I said, ‘Don’t worry, I’m going to bring it back from hell.’

‘I’ll support you in whatever you want to do,’ he said, ‘but just know that I think you’re mad.’

He wasn’t on his own. Everyone said pretty much the same thing. They thought boxing would be a phase, that I’d last a year or two and come back to footy.

I knew that wasn’t going to happen.

I was disillusioned with league. I felt like I kept getting denied time and time again. I was statistically the best five-eighth at the time. Some might debate it, but I believed – then and now – that I was the best in the game.

From my first season with the Dragons, I was making comments to try and bring the fight to me. I backed my ability. I said Laurie was running on old legs because I believed, one-on-one, I was the better player. He brought out the best in me.

It was the same when I came up against Freddy. We’d always had the wood on the Roosters, Mashallah, and when Freddy and me played against each other it was like a boxing fight. We would run straight at each other and I’d be like, ‘All day, bro, all day. I’m here. I’m not going nowhere.’

The straw that broke the camel’s back was when Laurie Daley and Brad Fittler weren’t available for the Tri-Nations in 1999. I thought, ‘I’m definitely next in line for a Test jersey.’ The Australian selectors ended up picking my brother, Matty Johns, who is a good mate of mine. Matty was a deadly player, but at the time I was a different animal to him.

It broke my spirit and my heart. I was like, ‘I’m out of here, man.’

More about: Anthony Mundine | Boxing World Champion | Brad Fittler | Jeff Horn | Kangaroos | Religion | Resilience | St George Illawarra Dragons

Load More

Load More